(by: Doug Van Dorn)

In this series, we are asking the specific question, “How do I read the Psalms?” After figuring out the level of reading you want to achieve, you need to move into specifics. Here are some of my thoughts as I’ve been studying the Psalms. I believe they are simple enough for a second level of reading (“chewing”), but profound enough to take you all the way to the highest level you want to go.

- Psalms is not a book about life-verses. Growing up in the 80s, singing the Psalms was becoming popular again. But this wasn’t a singing of the whole psalm. It was often a wrenching out of context of one or two “happy verses” to create a sentimental ditty. As the Deer is an interesting example. Taking its cue from Psalm 42:1, the song is a series of cheerful lines that fit a simple, welcoming tune. Many of those lines are taken from other parts of Scripture, which is well and good. But, this isn’t singing the psalm. Rather, the context of Psalm 42 is very, very different from anything you actually hear in that contemporary chorus. In fact, there actually is a chorus in Psalm 42 (it has one idea repeated three times). It isn’t “As the deer pants for the water, so my soul longs after you.” Rather, it is, “Why are you cast down, O my soul, and why are you in turmoil within me? Hope in God; for I shall again praise him, my salvation and my God” (Ps 42:5, 11, 43:5). That’s quite a different idea from “As the Deer…” So, as you read the Psalms, don’t go looking for a verse here or there. Read the whole thing and come to understand its main point.

- The Main Point. How do you find the main point of a psalm? There are several ways of doing this. Understanding the kind of literature that you are in is the place to start. Psalms are songs. These songs are written in Hebrew poetry. As such, you will find at least one of the following elements in each song:

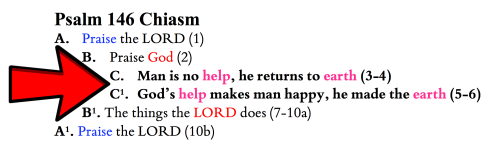

- Chiasm. A chiasm is the most basic and common technique employed by the psalmists (they are actually found throughout the Bible, not just the Psalms). In its most basic form, it is a repetition of ideas that form a

giant arrow pointing you to the main point. They used chiasms to help in memorization and to highlight various parts of the text. Most psalms are chiastic,[1] so look for repeating ideas near the ends of the song and inbetween. When you find a chiasm, the center is the main point. Once you become practiced at it, finding chiasms isn’t really all the difficult, even when you are simply sitting down and reading the psalm. In the paragraph I have provided an example from the most recent Psalm I preached.

giant arrow pointing you to the main point. They used chiasms to help in memorization and to highlight various parts of the text. Most psalms are chiastic,[1] so look for repeating ideas near the ends of the song and inbetween. When you find a chiasm, the center is the main point. Once you become practiced at it, finding chiasms isn’t really all the difficult, even when you are simply sitting down and reading the psalm. In the paragraph I have provided an example from the most recent Psalm I preached. - Repetition. When you notice a line repeated in a psalm (like we saw in Psalm 42-43), this acts like an English chorus (a line repeated throughout the song). This is rarer than chiasm, but many psalms have them. This is a main idea of the song.

- Superscription. The superscription is the first line of a psalm that was added later and is not, properly speaking, part of the text of the song. I believe the superscriptions are inspired. I also believe they are important for identifying the background of a song. Some are quite detailed (like Psalm 57’s, “To the choirmaster: according to Do Not Destroy. A Miktam of David, when he fled from Saul, in the cave”). Others are very basic (like Psalm 143’s “A Psalm of David”). Both help put the song in a context, and sometimes that context means you need to go to other places in the Bible to better understand what’s going on. In the case of Psalm 57, you need to read 1 Samuel 24. In the case of a simple Davidic song, just remember that this means the song is coming from the hand of the king.

- First and last verses. Since every Psalm has a first and last verse, look at these for clues as to the what the rest of the psalm will answer. A good and simple example of this is the Hallelujah psalms at the end of the book (Ps 146-150). Each of these psalms begins and ends with the word “Hallelujah” (in Hebrew). In between, you learn the reasons why you are to “praise the LORD.” Another example is a song we just looked at. “As the Deer…” (cited in the previous post) begins Psalm 42. This is its first verse. It is actually a very meaningful verse, integral to the song as a whole. The last verse also happens to be the chorus. So here we have two of our ideas in understanding the point of a song. When put together, suddenly, it is clear that this isn’t a mere sentiment the psalmist is giving you, but a deep act of faith that becomes the longing of his heart during great trials and suffering.

After looking for the main point(s) of a song, it is time to move onto the next phase of reading the Psalms, which is learning to read them beyond a rag-tag collection of randomly jumbled together songs. We will look at this in the next installment.

[1] I’ve used three main online resources in my preaching through the Psalms here. First, Robert Alden’s three-part series on chiasms in the psalms published several decades ago in the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society (Psalms 1-50, Psalms 51-100, Psalms 101-150). Second, a blogger named Christine who has done some tremendous work on chiastic psalms. Third, the Biblical Chiasm Exchange.

One thought on “How to Read the Psalms (Series): Part II of IV”