(by: Doug Van Dorn)

You have now decided what level of reading you want to achieve as you come to the psalms. You have learned some of the basics of how to understand the main point of a given song. And you now realize that there are multiple levels at which your reading can be done. Now it is time for what I think is the most important aspect of reading the psalter. What is that?

You are to read the Psalter like a Christian.

Throughout the NT, the Psalms are quoted, alluded to, or echoed in the Gospels, the history, the letters, and the apocalypse—the whole thing. The vast majority of the time, the Apostles are quoting the psalms with Christ as their focus. In one way or another, be it through prophecy or typology or echoing terms such as Name, Wisdom, or Glory (see my series on Christ in the Old Testament), they read the psalms as a book about Christ.

Even many educated people fail to understand that the Apostles, much less Jesus (Luke 24:44; John 5:39-40; etc.), aren’t just making this up. Some, for example, are arguing that their “Christotelic” hermeneutic is justified, even though it was not part of the original meaning of the book. I strongly disagree with this view and believe that when taken to its logical end, it actually destroys the meaning, and thus objective confidence in the Bible. I do not believe that the Apostles or even Jesus himself could just invent new meaning (I dare say that would be sinful), even if it was for a good and justifiable end. Instead, I believe the Psalter itself was always “Christocentric.”[1]

The psalter itself begs to be read this way, beginning in Psalms 1-2 and ending in Psalms 144-145 (and the concluding Hallelujah songs—146-150) and everything in between. Here is where we need to put together several things we have learned. I will focus only on the first two songs of the Psalter and the last two.

Psalms 1-2 form a chiasm with the first and last verse being the beginning and ending. The chiasm forms around the word “blessed” and “the man” that both songs describe. “Blessed is the man who walks not in the counsel of the wicked, nor stands in the way of sinners, nor sits in the seat of scoffers … blessed are all who take refuge in him” (Ps 1:1, 2:12).

From the earliest days of the church, the Fathers understood both songs to be about Christ. They weren’t  just making this up. Psalm 1 demands that someone perfectly obey the law; but no fallen person can do this. This strongly implies that someone must come who will. Psalm 2 is one of the most quoted OT songs, and it is about “the Son.” The “him” of the last verse is very clearly talking about the Son of God.

just making this up. Psalm 1 demands that someone perfectly obey the law; but no fallen person can do this. This strongly implies that someone must come who will. Psalm 2 is one of the most quoted OT songs, and it is about “the Son.” The “him” of the last verse is very clearly talking about the Son of God.

Now, one of the curious things about these two songs, besides this chiastic form, is that neither song has a superscription. This is extremely rare in the first “little book” where almost every song is “a song of David.” But the superscription is left off of these two songs, and scholars conclude (rightly so), that is it because these two songs act as an Introduction to the rest of the book. Put a little differently, these songs tell you how you are supposed to read the rest of the Psalter. And since they have as their focus the Son of God and the Man who obeys perfectly, they telegraph that the rest of the book is about Christ.

The last two songs of the Psalter, properly speaking, are Psalms 144-145. These are not the last songs of the book, but they are the last songs that do something other than praise the LORD (the last five songs act as concluding Postludes or Epilogues not only to the whole book, but to each of the five little collections). In an important recent study (it was his dissertation), Michael Snearly[2] stands on the shoulders of many who have come before him and argues in a new way that Book V (Psalms 107-150) is the climactic book of Psalter, because after all the suffering and doubt and prophecies and so on, it reaches the conclusion that the King introduced at the beginning of the book “Returns” at the end. Thus, Psalm 144 is about this coming King and Psalm 145 is about his coming Kingdom. This ends in a single verse doxology (145:21), which is then followed by five songs of Praise that conclude the Psalter.

Can you see how Psalms 1 and 2 introduce the need for a coming Man, a Son of God (the son of a King), and how Psalms 144 and 145 end on a prophetic note that a Messianic King is coming? This isn’t making stuff up. It’s the way the book was intentionally and knowingly put together. Everything in between is, in one way or another, about this (so also are the Hallelujah songs at the end).

This means, that at the most basic level of reading, the Psalms are not about you (though they are certainly for you). They aren’t even about David or the human author that wrote them. They are the songs of King Jesus. Yes, you, like the human author, can find hope and meaning in your own circumstances. But this is primarily because they are about Christ; they anticipate him and teach you about him.

This, then, is how you are to read the Psalms. When you read them first as the story of Christ put to music, then you will be able to understand your own situations in life better. As King, they teach you his rule over you. As Suffering-Servant they show you that he knows all your sufferings. As God they show you where thanksgiving and praise rightly belongs. And so on.

I hope that this brief series of posts has whet your appetite for diving in anew to one of the great books ever written and complied and that through it, your devotion and worship of the Triune God will be strengthened.

To dig deeper, feel free to go to my church’s website rbcnc.com/psalms and look around.

[1] The difference in “Christotelic” vs. “Christocentric” is, as I understand it, the difference between a re-reading of the original “purpose” (telos) in light of the Christ-event, a purpose that was foreign to the original context vs. understanding the original meaning of the text to have been about Christ (and the ways the authors quote the passages) all along, even if they didn’t understand everything about what that meant.

[2] Michael K. Snearly, The Return of the King: Messianic Expectation in Book V of the Psalter (New York: Bloomsbury, 2016).

the record and let it play until Side A was finished. (Yeah, I know, you can play D. J. even on a record. But it’s a LOT more work, and really only fun when you are scratching!) When you turned it over, you started Side B.

the record and let it play until Side A was finished. (Yeah, I know, you can play D. J. even on a record. But it’s a LOT more work, and really only fun when you are scratching!) When you turned it over, you started Side B. Stage. Concept albums are like symphonies with their various movements that often trade on a basic set of notes, or jazz compositions that improvise a riff for fifteen minutes. Listen to the first and last songs on the Third Stage, and you realize that Amanda and Hollyann are not only the only two girl-named songs on the record, but they have the same basic tune! The songs form a kind of chiasm!

Stage. Concept albums are like symphonies with their various movements that often trade on a basic set of notes, or jazz compositions that improvise a riff for fifteen minutes. Listen to the first and last songs on the Third Stage, and you realize that Amanda and Hollyann are not only the only two girl-named songs on the record, but they have the same basic tune! The songs form a kind of chiasm!

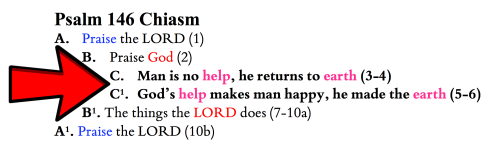

giant arrow

giant arrow